China’s international summit to help promote its strategic vision – ‘One Belt, One Road’ (OBOR), now dubbed the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – has just concluded in Beijing. Twenty-nine heads of state and representatives from 130 countries attended the two-day forum on 14-15 May. Most of Asia’s top leaders attend the gathering – including Myanmar’s State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi — as well as the heads of the United Nations, International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

However, India refused to send an official delegation to Beijing, because of their displeasure with China for developing a $57 billion trade corridor through Pakistan that also crosses the disputed territory of Kashmir. “No country can accept a project that ignores its core concerns on sovereignty and territorial integrity,” the Indian foreign ministry spokesman Gopal Baglay, reportedly said.

The Chinese hosts were keen to stress the economic value of this new international relationship that they want to forge, though it was also a chance to project China’s soft power. “We should build an open platform of cooperation and uphold and grow an open world economy,” China’s leader Xi Jinping told the opening of the conference.

And President Xi Jinping then pledged US$124 billion towards building his new Silk Road plan. This included an extra 100 billion yuan ($14.50 billion) for the existing Silk Road Fund, 380 billion yuan in loans from the two policy banks – especially the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) — and 60 billion yuan in aid to developing countries and international bodies in countries along the new trade routes. In addition, Xi said China would encourage financial institutions to increase their overseas yuan business to around 300 billion yuan.

In the forum President Xi Jinping called for cooperation amongst initiative’s members and for them to reject protectionism. China will seek a common prosperity with its ‘Belt and Road Initiative’, and not political dominance, he insisted. At the same time Xi called for the abandonment of old models based on rivalry and diplomatic power games.

The forum officially marked the grand opening of the Belt and Road Initiative, which originally comprised “the Silk Road Economic Belt” in Central Asia and “the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road” which intends to promote maritime routes that will connect China with South East Asia, South Asia and ports up and down the east coast of Africa.

Though regional linkages, like the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) will also be incorporated under Thailand’s initiative. Thailand’s Deputy Prime Minister Somkid Jatusripitak recently told a seminar of businessmen from Hong Kong and South East Asia that the EEC will link up with the One Belt, One Road initiative through the Thailand-China rail development project – Vientiane, Laos and Kunming, China.

Likewise transport links through Myanmar and Bangladesh are also a key part of the vision. This cooperation with China was agreed in 2013 with the establishment of the Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar (BCIM) forum, whose main purpose was to foster greater integration in trade and investment among the four nations involve. The corridor is an expressway that would link China’s Kunming to Kolkata in India through Mandalay in Myanmar, and Dhaka and Chittagong in Bangladesh.

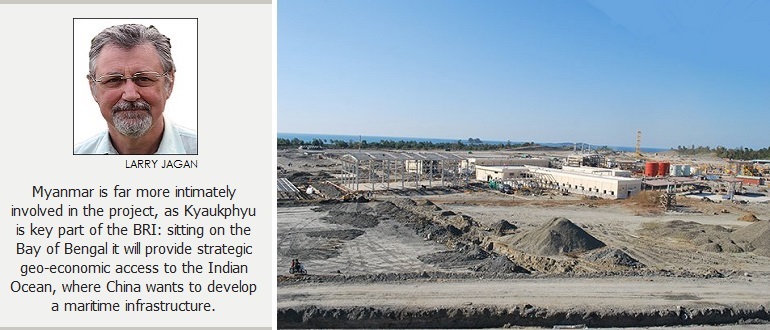

But Myanmar is far more intimately involved in the project, as Kyaukphyu is key part of the BRI: sitting on the Bay of Bengal it will provide strategic geo-economic access to the Indian Ocean, where China wants to develop a maritime infrastructure.

Kyauk Phyu is strategically crucial to the overall objectives of China’s belt and road project. The oil pipeline from the area has just started carry oil and gas for the fields of the shores of the area. Roads and rail lines from Kyauk Phyu to Kunming in southern China are also in the works. As well as developing a deep-seat port there. The Chinese are currently demanding more than 70 percent ownership of the development in this area.

Representatives of organizations from 68 countries signed the Belt and Road Cooperation Agreement with China at the conclusion of the event. The summit significantly also marked the emergence of China as the world’s second super power, besides the US. Until recently Beijing has been coy about announcing its superior position economically and politically in the international community. For years, they boasted that they were the leaders of the developing world, and not a ‘First Power.’

The BRI — as it is now called – is intended to invigorate trade and development in Asia, with China playing the leading role. Through trade and communication links, it hopes to bring together Asia, Africa, Europe, Russia, the Middle East and America. But more importantly it also marks a significant shift in the world order. It is China’s concerted effort to fill the power vacuum that many analysts believe is being left by US president Donald Trump’s isolationist policy of “America First”.

The summit was in fact China’s coming of age. The OBOR project has been in the pipeline for some time now. President Xi Jinping first unveiled the idea in 2013, since then it has been synonymous with the rise of China’s economy and its need for greater sources of resources and markets. The central focus was on the promotion of connectivity and cooperation among the countries involved in the project – with Beijing the centrifugal force.

After founding the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) with a capital investment of US$100 billion, China allocated $40 billion to the Silk Road Fund. Chinese financial institutions – like the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China – will also lend money to countries involved in the Belt and Road Initiative for the development of infrastructure.

As yet the full scope of the project is only generally defined. While it is obvious that it was an economic framework to connect China’s Silk Road Economic Belt project with its Maritime Silk Road through connected bodies of water from the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean. In essence, this framework intended to increase China’s connection with countries along the historical Silk Road in Eurasia, while creating a new Silk Road through Asia to South Asia and Africa.

One part of the project is centered on the creating of greater trade connections between China and Eurasia, including infrastructure projects ports, highways and rail lines. According to analysts the proposed increased trade links would cover 65 per cent of the world’s population, one-third of global GDP and a quarter of all the goods and services in the international economy.

But China’s vision and strategy is not without its critics. Many believe there is a thinly veiled intention for China to extend its political influence through the project. They suggest that there is no concrete demand for the OBOR’s infrastructure projects in under-developed central Asian countries in particular. But rather, China is building these projects as a way to extend and entrench its political influence, especially in strategic and sensitive areas. The same criticism has been quietly voiced in Myanmar – and in Laos and Thailand there is resistance to the rail and road links under construction. Community leaders have led grassroots protests against the Chinese penetration, and scant regard for land rights.

New maritime routes connecting China to the rest of Asia would also significantly expand Beijing’s economic and political power in the region.

For example, if a route can be built through Myanmar – from the ports of Kyauk Phyu, Moulmein and Dawei in southern Myanmar – this would save China time and money in getting its oil supplies from the Middle East. A canal across Thailand or a road through Thailand would certainly be a safer route for its crude oil imports from Africa and the Middle East. At present about 60 percent of China’s crude imports pass through the Strait of Malacca – something China wants to avoid in the future. For more than a decade Beijing has worried about the Malacca straits and have desperately looking for alternative routes for their imports of oil and exports of consumer goods.

The ‘One Belt, One Road’ idea is an international community project with China taking the lead. If the Chinese are able to convince countries – especially in the Asian region, then the Chinese strategic vision will be accepted as force for good – BRI could well become a vehicle to revolutionize global trade, and restore peace and stability to top of the international agenda.

Pakistan president, Nawaz Sharif, and a close Chinese ally, praised China’s “vision and ingenuity”. “Such a broad sweep and scale of interlocking economic partnerships and investments is unprecedented in history,” Sharif said. While Deputy Prime Minister Somkid Jatusripitak said the One Belt, One Road strategy initiated by Chinese President Xi Jinping four years ago would now result in significant benefits that would be felt far beyond China.

“The world is now stuck in uncertainty from changes to US international trade policy to the exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union, along with mounting challenges from global liberalization policies,” he said.

“One Belt, One Road is the new hope for the world.”

[Larry Jagan is a journalist and Myanmar specialist, based in Yangon. He is also the author of several books and many academic articles on Myanmar. He has spent more than forty years covering the Asia region. He was Asia editor for the BBC World Service for more than a decade.]