(SouthAsianMonitor Exclusive): For sovereign nations, denied the benefit of huge size and abundant resources, diplomatic autonomy is a valuable asset. When they have just one Big Power in the vicinity and little choice, they may end up as a satellite. But if they have multiple options, they would like to use smart diplomacy to make up for what they lack.

This is no different in South Asia. The smaller nations in the region can neither overlook India nor China. That is a point they often like to make — but cannot do so openly for fear of being misunderstood.

Bangladesh’s junior foreign minister Shahriar Alam, however, chose to stress that before Chinese president Xi Jinping’s visit to Dhaka in November.

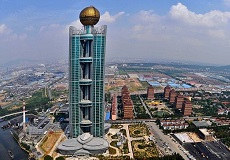

Both Xi and Bangladesh Prime Minister Hasina were to fly off to Goa (India) for the BRICS-BIMSTEC summit immediately after the Chinese president’s few hours’ sojourn in Dhaka., during which Beijing and Dhaka were signing up investment and project aid deals close to $ 28 billion.

“We need both India and China, we need to be friends with both of them, we don’t have a choice, ” Shahriar told this columnist in no uncertain terms. His leader and Prime Minister Hasina backed out of the SAARC summit due at Islamabad, pleasing Indian prime minister Modi who had turned the Goa summit into an elaborate exercise to isolate Pakistan. But she also ended up, during Xi’s Dhaka visit, upgrading the Sino-Bangladesh relationship to the level of a strategic partnership.

The message was clear — Bangladesh would go along with India and others like Afghanistan in taking on Pakistan because it was ‘unduly interfering in our internal affairs’. But China was a different cup of tea.

For a while, Bangladesh has strongly backed the China-driven BCIM initiative and also its One-Belt-One Road project. Dhaka sees huge economic benefits from these initiatives, especially in building regional infrastructure that would help it fulfill its own considerable development aspirations.

Those who denigrate Chinese aid-development funding as ‘cheque-book diplomacy’ miss the point. Beijing is not just throwing about its considerable resources for winning friends in the region. It has a larger vision for global and regional economic growth — albeit one with China at the center of it and in pursuance of its own national interests. The BCIM-OBOR initiatives are geopolitical and geo-economic manifestations of such a vision, in which small neighbors have a major role to play and much to benefit from. At least, that is the way they see it and no other country has so far echoed anything like that.

India is a much smaller economy and cannot imagine competing with China when it comes to ‘cheque-book diplomacy.’ Its $ 2 billion line of credit to Bangladesh is welcomed in Dhaka but fades into insignificance when compared to the Chinese $ 28 billion funding deals signed during Xi’s visit. The Western economies, including the US, has very little to offer to smaller South Asian nations like Bangladesh, surely not on a scale the Chinese can. So even a government run by Hasina, who depends considerably on Indian political support, cannot but turn to China for funding its considerable development aspirations.

The story is the same in Nepal and Sri Lanka, Maldives and Myanmar.

Nepalese Prime Minister Prachanda or Sri Lanka’s Sirisena needs Indian political support but Chinese development funding at the same time.

“We are not playing games with India, but we hope Delhi recognizes the reality,” one senior Nepali minister told this columnist, but on condition he is not named.

Myanmar’s pro-democracy icon and State Counsellor Aung Sang Suu Kyi also drove home the point after assuming power when she first paid a bilateral visit to China and then came to India for the BRICS-BIMSTEC summit. On the terrorism issue, however, Suu Kyi was less obliging to Delhi than Hasina and Afghan president Ashraf Ghani.

During her meeting with Indian leaders, she drove home the point that India should not try any trans-border raid on rebel bases by itself, as it claimed to have done in Myanmar’s Sagaing region in 2015. Since anti-Indian rebels are based in Myanmar, as they are in Pakistan, Suu Kyi as a democratically elected leader would naturally be more concerned about public reactions than a military leadership to Indian commando raids on her territory.

So India’s braggadocio about ‘surgical strikes’ may have been welcomed in Dhaka or Kabul because these countries suffer Pakistan-sponsored terror in some measure, but it left apprehensions brewing in Suu Kyi’s mind for understandable reasons.

Even before coming to power, she had objected to the Indian commando raids in an interview with India Today TV anchor Karan Thapar — ” we want nothing to happen behind our back”, she had told him.

Talk to any self-respecting leader in South Asia and broach the Sino-Indian rivalry and the answer one gets is that the region better be spared of such a rivalry. Most leaders in Bangladesh, Nepal, Maldives or Myanmar would echo Shahriar Alam’s ” we-need-both” stance. And what they seem to worry about is that though Modi’s arrival on stage initially promised better Sino-Indian relations, the opposite has happened. India has steadily slipped into the American orbit, emerging somewhat as the ‘pivot’ of Obama’s ‘Asia pivot’ strategy.

India’s decision to upgrade the military exercises with US and Japan, its support for the not-so-secret Tibetan-Uighur-Falungong conclave in a Himalayan town in early-2016, the open threat of its Hindutva-driven leaders to boycott Chinese goods are pointers — as much as China’s opposition to India’s entry into the Nuclear Suppliers Group, its funding of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and its efforts to bring Russia closer to Pakistan are signs of Beijing’s intransigence.

This is precisely what the smaller nations of South Asia do not want. They want India and China to be friends — and friendship with one is not seen as hostility towards the other.

Subir Bhaumik is a former BBC Correspondent and author